Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Darryl Boyd

Polymers pioneer is stitching sulfur into molecular strands to create advanced optics

by Michael Torrice

August 20, 2018 | APPEARED IN VOLUME 96, ISSUE 33

Darryl Boyd admits there’s a downside to the chemistry he works on. Most of his research at the U.S. Naval Research Laboratory involves sulfur compounds, which can smell like rotten eggs. “I never thought I’d be a stinky chemist,” he says.

Boyd has taken this pungent chemistry and used it to synthesize unique polymers with impressive optical properties that could be used in fiber optics, displays, and night-vision goggles.

“There is a lot of sulfur, but we’re not doing much with it,” Boyd says. In 2014, the U.S. produced about 9 million metric tons of the element, according to the U.S. Geological Survey, and much of that comes from processing petroleum products. Finding chemical applications for this surplus could help mitigate the environmental risk of sulfur stockpiles across the country.

Sulfur can also enhance the properties of optical materials, Boyd explains. For example, eyeglass makers add sulfur-based materials to lenses to increase their focusing power. As a result, lenses can be thin and still focus light properly for people’s eyes.

One of Boyd’s sulfur projects involves a process called inverse vulcanization. Normal vulcanization uses sulfur to cross-link carbon chains to produce more durable forms of rubber. Inverse vulcanization flips that process on its head by using carbon molecules to cross-link sulfur chains.

Boyd was the first to incorporate sulfur’s periodic table neighbor, selenium, into these polymer chains to create what he calls organically modified chalcogenide polymers. These materials could be used in infrared optics, such as night-vision goggles, and one of the materials that Boyd synthesized boasts the highest refractive index ever for an optical polymer.

Although polymers are his current focus, Boyd’s academic background is diverse, including work on organometallic synthesis and biochemistry. Being able to move from field to field has helped him innovate, says Frances Ligler of North Carolina State University, who was Boyd’s postdoctoral adviser. Boyd sees connections between fields and can apply knowledge from one field to another, she says.

For Boyd, his current work highlights what he loves about chemistry—the ability to create something new.

Watch Boyd speak at the American Chemical Society national meeting on Aug. 20 in Boston.

Vitals

Current affiliation: U.S. Naval Research Laboratory

Age: 36

Ph.D. alma mater: Purdue University

Role model: George Washington Carver because he was so diligent in hammering away at research topics he was interested in—the science of peanuts and potatoes. My postdoctoral adviser, Frances S. Ligler, because despite her many research achievements, she has such a humble approach to advising chemists and to pursuing new research ideas.

If I were an element, I would be: Vibranium. It's ductile, malleable, and conductive. It has great, shiny luster, it's superstrong, and it makes for great movies!

Latest TV show binge-watched: "Luke Cage" and "Riverdale"

Walk-up song: "Now's the Time" by Charlie (Yardbird) Parker

Research at a glance

Credit: Yang H. Ku/C&EN/Shutterstock

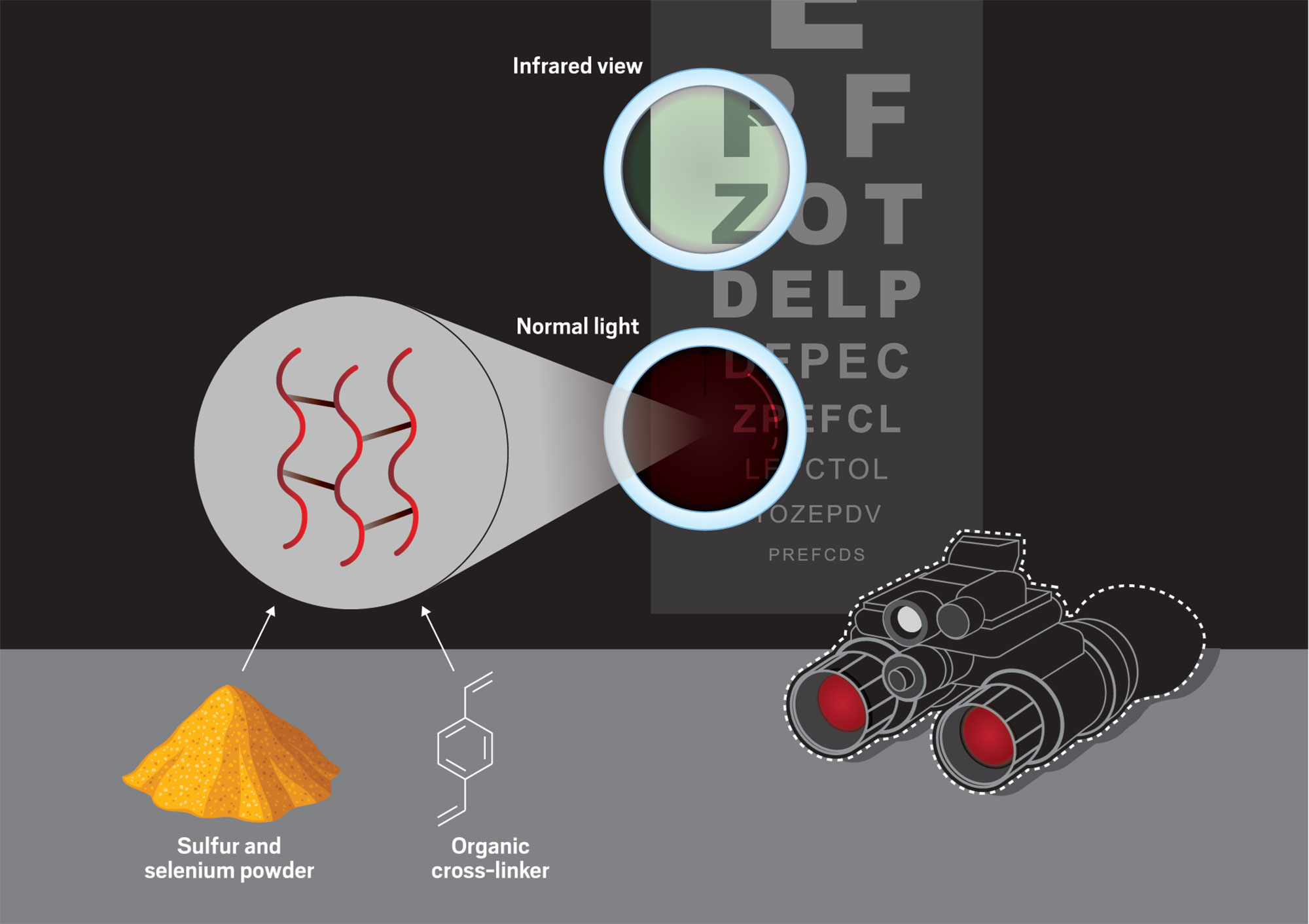

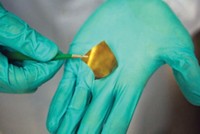

To carry out inverse vulcanization, Boyd heats sulfur and selenium powders with organic molecules. The resulting polymers, formed when the organic molecules cross-link chains of sulfur and selenium, are transparent to infrared light and could be used in applications such as night-vision goggles.

Three key papers

"ORMOCHALCs: Organically Modified Chalcogenide Polymers for Infrared Optics"

(Chem. Commun. 2016, DOI: 10.1039/c6cc08307b)

"Sulfur and Its Role in Modern Materials Science"

(Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016, DOI: 10.1002/anie.201604615)

"Hydrodynamic Shaping, Polymerization, and Subsequent Modification of Thiol Click Fibers"

(ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2012, DOI: 10.1021/am3022834)

Polymers

Darryl Boyd

Polymers pioneer is stitching sulfur into molecular strands to create advanced optics

by Michael Torrice

August 19, 2018

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 96, Issue 33

Three key papers “ORMOCHALCs: Organically Modified Chalcogenide Polymers for Infrared Optics” (Chem. Commun. 2016, DOI: 10.1039/c6cc08307b)

“Sulfur and Its Role in Modern Materials Science” (Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016, DOI: 10.1002/anie.201604615)

“Hydrodynamic Shaping, Polymerization, and Subsequent Modification of Thiol Click Fibers” (ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2012, DOI: 10.1021/am3022834)

Vitals

Current affiliation: U.S. Naval Research Laboratory

Age: 36

Ph.D. alma mater: Purdue University

Role model: George Washington Carver because he was so diligent in hammering away at research topics he was interested in—the science of peanuts and potatoes. My postdoctoral adviser, Frances S. Ligler, because despite her many research achievements, she has such a humble approach to advising chemists and to pursuing new research ideas.

If I were an element, I would be: Vibranium. It’s ductile, malleable, and conductive. It has great, shiny luster, it’s superstrong, and it makes for great movies!

Latest TV show binge-watched: “Luke Cage” and “Riverdale”

Walk-up song: “Now’s the Time” by Charlie (Yardbird) Parker

Darryl Boyd admits there’s a downside to the chemistry he works on. Most of his research at the U.S. Naval Research Laboratory involves sulfur compounds, which can smell like rotten eggs. “I never thought I’d be a stinky chemist,” he says.

Boyd has taken this pungent chemistry and used it to synthesize unique polymers with impressive optical properties that could be used in fiber optics, displays, and night-vision goggles.

“There is a lot of sulfur, but we’re not doing much with it,” Boyd says. In 2014, the U.S. produced about 9 million metric tons of the element, according to the U.S. Geological Survey, and much of that comes from processing petroleum products. Finding chemical applications for this surplus could help mitigate the environmental risk of sulfur stockpiles across the country.

Sulfur can also enhance the properties of optical materials, Boyd explains. For example, eyeglass makers add sulfur-based materials to lenses to increase their focusing power. As a result, lenses can be thin and still focus light properly for people’s eyes.

One of Boyd’s sulfur projects involves a process called inverse vulcanization. Normal vulcanization uses sulfur to cross-link carbon chains to produce more durable forms of rubber. Inverse vulcanization flips that process on its head by using carbon molecules to cross-link sulfur chains.

Boyd was the first to incorporate sulfur’s periodic table neighbor, selenium, into these polymer chains to create what he calls organically modified chalcogenide polymers. These materials could be used in infrared optics, such as night-vision goggles, and one of the materials that Boyd synthesized boasts the highest refractive index ever for an optical polymer.

Although polymers are his current focus, Boyd’s academic background is diverse, including work on organometallic synthesis and biochemistry. Being able to move from field to field has helped him innovate, says Frances Ligler of North Carolina State University, who was Boyd’s postdoctoral adviser. Boyd sees connections between fields and can apply knowledge from one field to another, she says.

For Boyd, his current work highlights what he loves about chemistry—the ability to create something new.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter