Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Recycling

Movers And Shakers

Shay Sethi talks about the future of fabric recycling

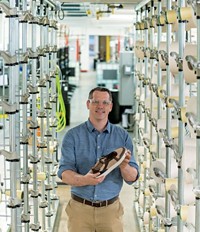

The cofounder and CEO of Ambercycle wants to shake up the fashion industry with a new textile recycling process

by Prachi Patel, special to C&EN

March 14, 2021

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 99, Issue 9

Clothing might not come to mind when people think of plastic pollution. But polyester, derived from crude oil, makes up half the total fiber used in the global manufacture of textiles for apparel, upholstery, and other products, according to an analysis by IHS Markit. Less than 1% of garments get recycled into new clothing, and around 38 million metric tons of polyester from the fashion industry ends up in landfills each year, according to Shay Sethi, CEO of the start-up company Ambercycle.

Adding value to textile trash is the only way to keep the world from drowning in it, he says. He and his former college roommate, Moby Ahmed, developed a way to recover the natural and synthetic polymers in textiles while they were students at the University of California, Davis. They cofounded Ambercycle in 2015 to scale up the process and show that it could be done cost effectively. In 2016, they won the H&M Foundation’s annual Global Change Award, which helped fund technology development. The company launched a product line of recycled garments with Los Angeles–based street-wear brand Come Back as a Flower in December.

Vitals

▸ Birthplace: Denver

▸ Hometown: Los Angeles

▸ Studies: BS, biochemistry and molecular biology, University of California, Davis, 2015

▸ Childhood dream: “Never really had one. For me, the question was ‘What’s tomorrow going to look like?’ I remember choosing my major and always felt I was good at science, but it was never like I wanted to be a scientist.”

▸ Favorite item of clothing: A simple black T-shirt. “I don’t personally wear high fashion; it’s a lot of street wear.”

▸ Why wear recycled clothing? “Because it’s cool. It’s sexy. Blending science with art always sounds nice. Regenerated clothing is the future, and who doesn’t want to live in the future?”

Sethi says the toughest task is to make the cost of recycled polyester competitive with that of virgin polymer, at $1 per kilogram. This is achievable by getting to commercial scale, but it takes time to get there, he says. Prachi Patel talked with Sethi about the challenges of shaking up a big, established industry. The following interview was edited for length and clarity.

What is the problem Ambercycle is trying to tackle?

The waste management industry has not seen much technological change. Plastic water bottles are very clean materials, so you can recycle them using rudimentary technology—basically just melting and re-forming. It’s very archaic.

Most of our fabric today—T-shirts, furniture, carpets—is some form of polyester blended with cotton or acrylic or spandex. This makes it really hard to recycle. Ambercycle is developing an advanced recycling process for these textiles. Old garments come into the process and are converted to their initial constituents, and those molecules can be used to make the same garments. We recycle the polyester and have partners who handle the cellulose and spandex components.

The idea is to build really elegant recycling processes using advanced chemistry and engineering and build a better back end for disposing of things and making new stuff. We’re starting with polyester in textiles but will expand to make other polyester streams circular as well. We are part of a new wave of improved circular materials companies that can better recycle these complex materials.

What is the recycling process?

It’s essentially a molecular separation of the different components in a garment. A whole T-shirt goes into a reactor, and through a patented process, we are able to recover the polyester and re-form it into a yarn.

Our process is a combination of existing chemical recycling with clever engineering that makes the process continuous. It’s simple, fast, and not energy intensive. Making virgin polyester from oil takes a lot of energy. Our process consumes 80 to 90% less energy per kilogram of material produced. Every industrial process dreams of a 98-plus percent yield, and we’re getting there.

Right now, we are running a pilot plant that processes tens of kilograms of clothing a day to verify the technical process. And we are building a demonstration plant that will produce a metric ton of material per day; that’s 10,000 to 15,000 garments. We’ll prove our idea with the demonstration plant and then find partners for a commercial plant.

Does recycled clothing face mainly technical challenges or market barriers?

It’s a little bit of both. It’s not enough to rely on the science. If you have new technology, you also need to have a way to introduce the product into the marketplace. You can’t force sustainability; it has to be a desire. Creating that desire has been a perplexing challenge for the larger cause of moving to circularity.

If you have two T-shirts in front of you and one of them is made from virgin resources and the other is made from sustainable or recycled ones, then all else being equal, people will choose the sustainable one. The hard part is to make all else equal—equal in convenience, cost, quality, and appeal. It has to compete with oil. We are figuring out the technical puzzle pieces to make that choice equal.

What are your biggest challenges, and how do you plan to confront them?

It’s easy to make a material but very hard to make a systemic change. Figuring out the best way not just to make the materials but also to make a recycling ecosystem that is actually good is the big challenge. In Los Angeles, we’ve tried models where we’re collecting clothing from and delivering it to people’s houses. Imagine a food delivery service, but instead, a person comes to your door with new goods and takes away old goods. We’ve also tried deposit boxes for garments on a very small scale. We don’t have an answer yet, but we’re working on it.

We are working with large engineering firms to build our demo plant. We also have a lot of different partners through the apparel supply chain who we are working with closely to convert our raw materials into finished garments for brands.

On the financing side, we’ve been lucky and had success getting adequate funding. Fancy has never been a goal for us. We have enough resources to build a plant for now. We’re focusing on making it work and getting it to scale.

What impact do you hope to have?

The world needs to move to a circular economy. If we could help encourage that, get customers to look at their trash in a different light and say, “Hey, there’s value for this with advanced recycling,” that would be an ideal outcome and a tremendous win.

Prachi Patel is a freelance writer. A version of this story first appeared in ACS Central Science: cenm.ag/sethi.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter